Rampuri Baba, born William A. Gans (July 14, 1950), an American expatriate, has lived in India since 1970, when be became a Naga Sadhu (a Hindu monk of Naga tradition). He became the first foreigner initiated into ancient order of Naga Sannyasis. He is the author of the 2010 book Autobiography of a Sadhu: A Journey into Mystic India, (originally published in 2005 as Baba: Autobiography of a Blue-Eyed Yogi), which has also been translated into German and Russian.

Rampuri Baba "Westerners are constructing their own yoga and tantra"

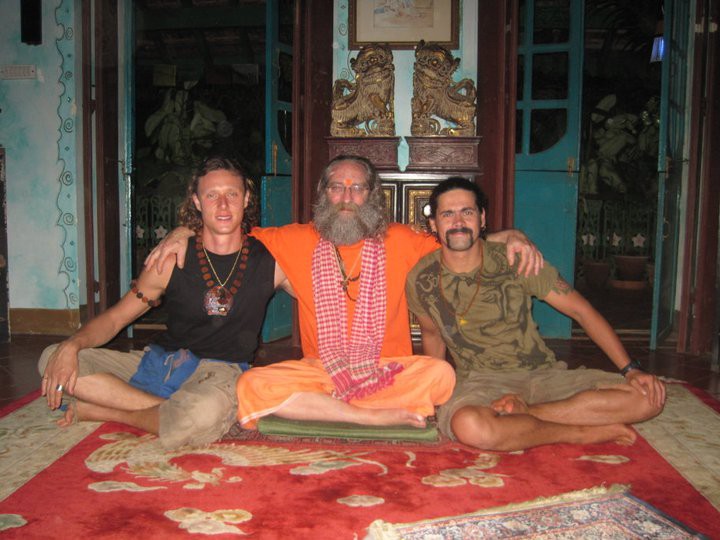

Talks with Ilya Zhuravlev and Tim Rakin

Ilya: Our last interview was in 2006, so what has been happening in your life since then? What about your books, your teachings?

Rampuri: During the last few years I have had an exposure to social media, through which I have been able to participate in many conversations on internet, hear a lot of thinking on internet from people who are interested in yoga and Indian tradition. It informed me about which seems to be going on in modern movements of yoga and spirituality not just in the West but also in India now.

Ilya: My next question is about the western yogis. Nowadays many westerners are practicing yoga and even though many of them are interested in Indian tradition, they yet seem to view yoga as a complex of exercises to improve their health. Most of them treat Indian stories as mere fairy tales and think of India as a country of magical stories and fables. Even having accepted the basic principles of dharma, westerners find it difficult to become blind believers like simple Indian people. This question dates back to the times of first westerners coming to India and starting yoga practice, so what is your opinion on that?

Rampuri: The way I see it is whether foreigners see it as fantasy because of disbelief or whether they completely believe it - I think both sides are fantasies. I think there are very few people in the West who are capable of seeing anything in Indian culture. I think that in fact the western knowledge of Indian culture is autobiographical. When western people are describing India they are actually looking in the mirror and describing themselves. This is because of the nature of our cultures, that is the western world represents the rest of the world, it speaks for the rest of the world, it’s the agent of it. The western world doesn’t see that the rest of the world is capable of representing itself, for speaking for itself, so it must be spoken for. So, this is the foundation from which we look at eastern culture, Indian culture, discuss it and get into it. So, from the very beginning we are in trouble.

Now, having started in the beginning, we super impose on our quest many assumptions that we don’t examine very carefully. For example, a very common assumption is that sacred text is one of the main focuses of study of Indian culture mysticism or esotericism. Of course, this is a conclusion, an assumption that we should bring into looking at India. Why? Because how do we study, how do we acquire knowledge in the West? We go to school, and then they send us home at night where we have to read so many books with so many pages and at the end of the week they give you an exam on which you have read the book and if you memorised it well - then you get a good mark on your exam and if you didn’t memorise it well - then you don’t get a good mark. So, from the beginning we make an assumption that the way that one acquires knowledge is by studying, by reading.

Next thing is that we look at major religion, that informs us about religious behavior and activity, which is Christianity, and we notice that in fact on the basis of Christianity the category of religion is defined and that category of religion basically has a sacred text as it centre piece, a sacred text, a deity and a doctrine. So we assume that in looking at another religion, such as the religions of India, that it too must posses a sacred text and that sacred texts must be central to practice of religion or mysticism. We in the New Age bring in an assumption of what is called perennialism, that all mystics are basically having the same experience, that all religions are talking about or having as their goal the same thing. And this is almost entirely unquestionable in the New Age and the yoga movement. And yet, how do we come to that determination?

Probably the first person I know of, that made this point very strongly was Aldous Huxley in 1946 in his book called “Perennialism”. In his book he made an effort of collecting the quotations from texts from all different part of the world, from all different cultures and religions. And he juxtaposed them next to each other and sure enough be reading all those quotations from all different cultures and religions we see that “Oh my God, it looks like they are talking about one and the same thing!”. But what we don’t consider is that he selectively chose passages from all the religious texts and that all those religious texts were translated into English and of course all things look the same.

The problem with perennialism and sort of universialism is that the more you come up with the elements that seem to tie all the religions together, the more dilute that religious experience becomes and in the end by the time when you can tie everything together the end product is unrecognisable by any of the traditions. This is Christian idea as well as political. This is politics that there is one God and that God I have a connection with and if you think you have a separate God you are wrong, because my God is the true God. And this is way oversimplifying of course, but at the end of the day this is basically what is in operation. And with diversity allowing authority to be local instead of universal this does away with that problem and I think a considerable matter of politics. So, we bring many assumptions into looking at Indian culture and the assumptions basically are so numerous and so all encompassing that what is left is nothing, you have no room to move, you are squeezed in to a tight room of your assumptions and there is little left to be explored. This is the what the weakness is.

Tim: So, tell me, as a person who knows India from the inside - is there what we, westerners, call magic?

Rampuri: You see, we are running up against the same problem again, which we are going to continue to run up against. And that is that we have a structure with dealing with this material that is different from dealing with this material in a traditional culture. We are referencing science, for example, as the normative paradigm, as the normal situation, and then we see something that is unexplainable by science and we treat it as magic, because it is not science and yet we experience it, so it is magic. But you see, we are framing the question and we are framing the experience in terms of science, we are already making an assumption that science is the normal. Now, if you take, say, yogi in Himalayas, he is not taking science as the normal, that doesn’t mean he doesn’t believe in science, that he doesn’t use science, of course, he uses it, but his normal is the mythological world, his normal is the magic that happens out of guru disciple relationship, the tradition of this relationship. So, when there is something extraordinary happens, the person whose normal is science would call it magic, the yogi might call it revelation. Not magic, but revelation. So, in other words the beholding would be what they call in Hindi or Sanscrit “Darshan” rather than “Magic”. It is the difference of orientation. It is very comfortable for western audience to fictionalise Indian yogis, but where does it get us unless we are selling the film rights, if you know what I mean. It is crucial to identify the assumption, to identify who we are, who is asking the question, even though it may be very difficult to exercise. Because, whoever is framing the question is predetermining the answer.

Ilya: You have once during one of our talks interestingly pointed out the role of Vivekananda in creation of the modern yoga for the West, which in fact was his mission articulated by his guru Ramakrishna. Nowadays, we can see that physical yoga as well as some parts of Hindu tradition becoming more and more popular in the West, often taking different forms depending on the surrounding environment. There is, for instance, such thing as “Californian Hinduism”, for example Bhakti Fest in California, where the stage is built in the middle of the desert and over 2 thousand people come to dance and chant mantras. It rises a question whether it is only a matter of fashion, or these people have some sort of a karmic connection, why do they sing bhajans without even understanding the meaning of lyrics? May be without even realising it, people are drawn to Indian tradition by karmic connections, or it is merely in vogue these days? What is your opinion?

Rampuri: Look at the ways that western people practice these things - they are all physical ways, whereas in terms of the mental, or let`s even call it the non-physical, western people have no access to whatsoever. Physical is hatha yoga and anyone can learn physical exercises.

Ilya: But kirtan is not exercises.

Rampuri: Kirtan is singing. Everybody sings, everybody has been either in church or in a rock-n-roll concert, singing in a shower or bath, everybody can sing - you just listen to the tune and find the words. And all this clapping and dancing or whatever people do during bhajans or kirtans, which anybody can do, because there is nothing that has to go on outside of the physical realm. So, any place where you find physical realm sure enough westerners can participate completely, westerners can become very good Indian musicians, Indian dancers, hatha yogis. But when you enter into the non-physical realm, which includes the mental, the spiritual and all these kinds of things, then unless the western person does a very serious deconstruction and identifies all the baggage, all the assumptions, all the mythology that one brings into a quest, it is just impossible, because the conclusions you reach are from looking the mirror and not from engaging the other. It is by projecting the same rather than engaging the other. This is what separates these two realms.

Ilya: So, are you implying that there is no connection whatsoever between the people singing “Om Namah Shivaya” in California and of those in Himalayas?

Rampuri: Well, obviously the syllables are the same, so there are resemblances.

Ilya: So, in your opinion people, following “Californian Hinduism” can`t have real Bhakti or darshan of some deity?

Rampuri: I think they can have darshan of a deity and I think that they can perform Bhakti and they can do all those things, but the way that mysticism is measured in the West today, and this is another assumption that we bring in, is that mysticism is measured by experience and it is experience that describes mysticism. Again, going back to what I`ve said before - experience is constructed and if you construct a world which allows a darshan of Ganesh, then of course you can have darshan of Ganesh. If you construct a world where enlightenment is closing your eyes and seeing neon golden Om, then you basically can have any experience that you construct in yourself. So, it is very curious that different people of different religion have a mystical experience that is consistent with their tradition - Mother Teresa had a vision of Virgin Mary and not of Shiva and Himalayan yogi has a vision of Shiva and not of Christ. So, people can have any experience, but it is not separate from how they construct their way of having experience, the way that they build their cultural artifacts, knowledge artifacts, linguistic artifacts that is all is going to determine their experience in the end.

Ilya: So, no assumptions for westerners - no Shiva, no mantras, no rudraksha beads?

Rampuri: Of what use are the assumptions when there is darshan? You must understand, that what I`m saying is not that you should loose or give up your assumptions, but to question and identify them. Once you have identified your assumptions and framed the question, then what you are examining opens up on its own. Categorising assumptions as something bad because they colour our experience is a feature of a post-enlightment modern world called moralism. Do not give up anything but just be aware that such things exist.

If we are through cultural and linguistic conditioning are determining our experience - if Christian mystic have revelations of Virgin Mary and Hindu mystics have visions of Shiva is there such a thing as pure experience? What is curious is that this I can see as a dividing line between modern western discourse at its higher angles, at its higher reaches and traditional India, because I think that it`s pretty much unanimous in western discourse that it`s not possible to have a pure experience, that pure experience does not exist. But you have to bare in mind, that people who are determining this are members of the academy, they a disciplined people and they have methodologies of their thinking. And in their methodologies of thinking the articulation trust and belief does not exist. So it is not a issue that they have or don’t have a trust, in Indian tradition on the other hand even the constructivists or whom you might identify as such, they allow the possibility of pure experience. So what we do, is we take this idea of pure experience and turn it into an ideology, which is not what is done in Indian tradition, where pure experience is not in terms of ideology.

Ilya: Now, I would like to talk about the contemporary issues of the yoga movement from different perspective. What we see now, is that even many of the Indian yoga teachers start to copy western yoga teachers.

Rampuri: But if you look at the very first Indian yoga teachers they were all very westernised people: they all spoke English, they were all from somewhat urban middle or upper-middle class backgrounds and what they started with was very much western influenced and surprise-surprise western people liked it! It somehow seems familiar, comfortable and right. Isn`t this incredible that something from so far away can seem so right. There is a good reason for that, because it was built on a Western structure to begin with. So, then the western people take it back to the West and now again it`s coming from the western people to the Indian people, because what Indian people can bring to yoga is authority and this is a difficult thing for people in the West to establish themselves. So what happens is that you take a Baba, for example a particular a youngish Baba in his mid-thirties and he gets invited to go overseas. He goes overseas to a European country and everyone wants him to teach them yoga, but not Hinduism. So, over the next couple of years he learns the yoga, the hatha yoga, that people do in the West from a couple of his students and becomes a successful yoga teacher in Europe because he is seen as the authority. And I`ve discussed this issue with the Baba and he replied that these people don’t want to learn Indian tradition they just want to learn hatha yoga and so he teaches them that.

So, what I have obtained from my numerous conversations about the western yoga is that there is a focus on a Krishnamacharya teaching of intensive asana practice, there is a focus on tantra also, but the focus is completely misplaced, because what they are talking about in terms of tantra is as much a construction as the way they are constructing yoga.

Anjuna, Goa, winter 2011

Rampuri Baba's website: rampuri.com