In the ultimate sense, the goal of yoga (which means union) is the realisation that the individual consciousness is one with universal consciousness. This is a very lofty goal for most of us. A more achievable goal in the short term is to maximise communications between the brain and the body through yoga practice. To make your yoga as effective as possible, it helps to understand the anatomy of what you are trying to achieve and what yoga can do.

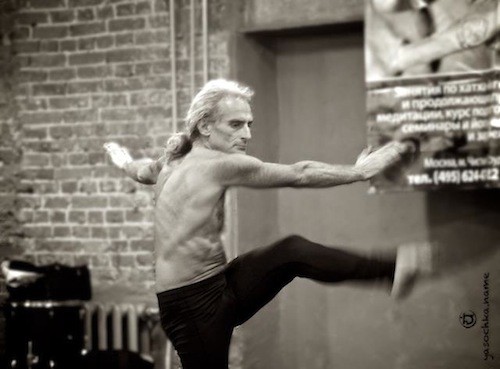

Simon Borg-Olivier. "The anatomy of yoga: closing circle of brain-body communication"

Brain-body communication

Good communication between your brain and body allows you to enhance health and vitality and to recover from injury more easily. The main means of communication in the body is via the circulation of energy (prana) and information (citta) through the circulatory channels of the body. Hatha yoga is the physical form of the ancient Indian science of yoga that uses physical exercises (among other things) to help achieve the union of brain and body and enhance the communication between them.

The word hatha literally means force. Hatha yoga uses physical exercises to generate forces through the body that can enhance circulation. To achieve this, it helps to have complete control of the muscles and joints. A basic, practical understanding of anatomy can enhance your yoga practice immensely. This knowledge can also be used to improve your strength, flexibility, cardiovascular fitness and ability to heal injuries and to relax and meditate.

Yoga for ‘Western’ bodies

Traditional yoga is taught with the assumption that those practising it have typically Indian bodies. Generally, in the Western world, where yoga has become very popular, this is not the case. Generally, people living in India have a natural balance between their strength and flexibility. For example, they can very easily come to the squatting position, something they have been doing since they were children. Similarly, they can readily do the lotus position because of a lifetime of sitting cross-legged on the floor rather than on chairs.

Many traditional yoga sequences place deep squats and full-lotus or half-lotus postures relatively early on in the sequence without allowing much time to warm up the hips, knees or ankles. These postures are not considered deep or difficult stretches for the typical Indian body. Yet they are often quite difficult for Western bodies.

One misconception of yoga is that it’s all about stretching and relaxation. In fact, learning how to activate (tense) muscles and strengthen the body is as important as learning how to stretch and relax muscles. To achieve the healthiest physical body and the best physical yoga, you need to have a controlled balance between strength and flexibility as well as the ability to relax.

Anatomy of yoga

There are more than 200 joints and more than 600 named muscles in the body. To achieve a simplified but functional understanding of the body, it helps to think of the body in terms of nine main joint complexes and about 20 pairs of opposing muscle groups.

A joint complex is a set of joints that work together in the body and behave as one joint. For example, the elbow joint-complex is actually three joints working together at the elbow; the shoulder joint-complex is actually four joints that essentially work as one to move the arm relative to the body or to move the body relative to the arm. The nine major joint complexes in the body are the ankles, knees, hips, lower back, upper back, neck, shoulders, elbows and wrists.

A muscle group is a set of one or more muscles that all do the same job around a joint complex. For example, all the muscles that can bend (flex) the elbow joint-complex are called elbow flexors and all those muscles that can straighten (extend) the elbow joint-complex are called elbow extensors.

When you are stretching a particular muscle group, it’s important to consider the opposing muscle group — the muscle group opposing the action of the muscle group that is being stretched. Muscle groups generally work as opposing pairs. When one muscle group is lengthened or stretched, the opposing muscle group is shortened. The importance of this will be seen soon.

To practise yoga with a balance between strength and flexibility, it’s also essential to know how spinal reflexes work. A spinal reflex involves nerve impulses being passed into the spinal cord and a responding message, such as the relaxation or activation of a muscle, being sent out straight away, without any input from the brain. There are three important spinal reflexes involved in practising yoga: the myotatic (stretch) reflex, the reciprocal relaxation reflex and the inverse myotatic (relaxation) reflex.

The stretch reflex

The stretch reflex causes a lengthened muscle group to become tense if it is suddenly stretched. You therefore need to block this reflex in your yoga practice while trying to stretch a muscle. The stretch reflex can be blocked by:

- Mentally focusing on the muscle group being stretched

- Exhaling as you stretch

- Moving slowly into a stretch - Using the shortened muscles to actively move the joint complex into the stretched position (which causes reflex reciprocal relaxation — see below).

For example, it’s sometimes difficult for people to tense the abdominal muscles, so if you first activate the muscles under the rear armpit (in particular Latissimus dorsi) by pulling the shoulder closer to the hip, this pulls on the tissues around the lower trunk that attach to and blend with the abdominal muscles. This makes it easier to activate the abdominal muscles and stabilize the lower trunk.

The stretch reflex is used to help us maintain an upright posture and is at work all the time when we are upright. When we are standing, if the body leans forward, the calf muscles stretch and cause a stretch reflex activation that causes the calf muscle to shorten and bring the weight back onto the heels. Similarly, if we lean back, the muscles at the front of the shin stretch, causing a stretch reflex activation of these muscles to shorten, pulling the weight back into the front of the foot and maintaining balance. Keeping muscles slightly tensed in yoga postures helps to increase the sensitivity of stretch-reflex receptors and improves balance and co-ordination.

The reciprocal relaxation reflex

The reciprocal relaxation reflex causes the stretched muscle group to relax when the shortened muscle group tenses. This reflex can be employed to help you relax and stretch any part of your body.

Stiffness in the knee flexors, the muscle group at the back of the thighs (hamstrings), is often released by tensing knee extensors, the muscles at the front of the thighs (quadriceps muscle group). This can be done in a straight-legged forward-bending position by simply pulling up the kneecaps.

Tensing the opposite part of a joint complex can often relieve a tense or painful part of the body. For example, pain in the muscles that normally pull the shoulders up towards the ears (muscles on the side of the neck) can often be relieved by actively pulling the shoulders down towards the hips.

The relaxation reflex

The relaxation reflex causes the stretched muscle group to relax if it’s stretched a sufficient amount. This usually takes place after a minimum of 12-15 seconds. However, if the muscle is tensed for a few seconds or more while it’s being stretched, it can take place within a few seconds. So, if you tense the stretched muscle, it not only strengthens the muscles involved but also stretches them further and allows them to subsequently relax more easily.

For example, if you are doing a forward-bending posture such as cross-legged forward bend, it’s mainly the hip extensors (buttocks muscles) that are being stretched. To rapidly get the effects of the relaxation reflex in this, you can choose to either tense the buttocks or tense the hip extensors by trying to extend the hip from a flexed hip position. In the cross-legged forward bend, this is practically achieved by trying to press the feet into the floor.

Another example of a position where the relaxation reflex can be used is the lunge or hip flexor stretch. In the lunge, you can tense the hip flexors while they are being stretched by trying to press the two feet together or by trying to squash the mat with your feet. This action stimulates the relaxation reflex, helping to stretch the hip flexors quickly and effectively, while also strengthening them. Later, it also allows them to relax more easily. Similar but more complicated processes can be applied in the advanced balancing lunge.

The balance of yoga

The techniques of hatha yoga eventually allow you to control each muscle enough to be able to generate relaxation or tension at will. As we age, it’s common that some parts of our body become more flexible and less stable while other parts are rarely moved and become relatively stiff. Yoga aims to equalise the forces around each of the main joint complexes in the body by getting the muscle groups into a state of balance.

Depending on the situation at each joint complex, a yoga practitioner can choose to either tense or relax either the shortened muscle group or the stretched muscle group. At the simplest level, the adept yoga practitioner can balance the forces around a joint complex by adopting any one of four states of activation or relaxation:

State 1

The shortened muscle group and the stretched muscle group can both be relaxed. This requires minimal physical effort but usually encounters resistance from the stretched muscle because of the stretch reflex and does not offer any additional stabilisation to the joint complex.

In certain situations, such as when there’s a muscle spasm, it’s appropriate to let both opposing muscle groups be completely relaxed and to safely hold each stretch long enough for the stretch reflex to be overridden by the relaxation reflex. This often takes minimal effort and allows a release of the mind as well as the body.

State 2

The shortened muscle group can be tensed and the stretched muscle group can remain relaxed. This helps to strengthen the shortened muscle and stimulates the reciprocal relaxation reflex, causing easier lengthening of the stretched muscle group.

If there is tension or pain on one side of a joint complex, it can often be alleviated by activation of the muscles on the opposing side of that joint complex. This can actually be used on either side of a joint complex to help reduce pain or inflammation, which is often present.

State 3

The stretched muscle group can be tensed and the shortened muscle group can remain relaxed. This helps to strengthen the stretched muscle in a lengthened position and stimulates the relaxation reflex, leading to an increase in the stretch and subsequent increase in the ability of the stretched muscle to relax. This can also stimulate the reciprocal relaxation reflex in the shortened muscle group, helping to relax it and rid it of any unwanted and sometimes pain-producing tension.

Tense or very stiff muscles, which may elicit joint pain, can often by relaxed by actively tensing them when they are in a lengthened state. This can be enhanced if the muscle is further stretched by physically pressing on various parts of the muscle.

State 4

This is when both the shortened muscle group and the stretched muscle group are tensed. This gives stability to the joint complex, helps to regulate circulation and helps improve strength, flexibility and the ability to relax all the muscles involved.

If there is instability in a joint complex, co-activation (simultaneous tensing) of opposing muscles around the joint complex can strengthen and stabilise that joint complex and help to regulate circulation through that region. This can promote healing.

The benefits of proper practice

Co-activation of opposing muscles around joint complexes (bandha) provides the strength and stability to safely perform advanced yoga postures, and to assist the flow of energy throughout the body. Practitioners of martial arts, gymnastics and even classical ballet are instructed and observed to maintain muscle tone in their limbs when they perform extreme movements and stretches. This muscular tone is often also clearly visible in advanced yoga practitioners who can safely perform the more difficult asanas.

Studies on the stability of spinal joint-complexes, such as the lumbar spine (lower back) joint-complex, have demonstrated that a joint-stabilising effect from the co-activation of opposing muscles of the lower back and abdomen can reduce the risk of lumbar spinal injury and help minimise lower back pain.

This concept of co-activation of opposing muscles can be expanded to other joint complexes. If a weak region of an upper or lower limb joint-complex is not supported by some muscular activation or strength when that joint is moved to an extreme position (stretching), the weakest part of the joint will probably be the first part to move and maybe the only part of the joint to be stretched at all. Hence, many stretching exercises that are extreme in nature, and are not supported by some muscular activation or strength, are at risk of damaging joints.

The concept of yoga as a type of union can be seen in the spinal reflex system that completes a circuit by uniting the body (muscles) with the brain (or central nervous system). To know how and when it’s appropriate to apply these principles as a therapy in a safe and effective manner, you need a practical understanding and regular personal practice of yoga learned from an experienced teacher.

Special thanks to Alex Armstrong (Director, Flow Yoga, Perth) for his comments and suggestions for this article.

References: Borg-Olivier, S.A. and Machliss B.E. "Applied Anatomy and Physiology of Yoga" Yoga Synergy, Sydney 2005.

Also possible online course of Simon and Bianca on anatomy and physiology of yoga

Photos by Olga Sydorenko at the first workshop of Simon in Moscow, July 2012

Yoga Synergy, Sydney www.yogasynergy.com